Gear Week: Full Frame of Crop Sensor?

Throughout the week, I’m writing a series of posts about buying gear. As we near the end of the semester with graduations and holidays approaching, the number of questions I get from students about putting together a kit skyrockets.

When it comes to professional-class cameras, there are two distinct options within each of the major manufacturers lines: full frame or crop sensor cameras. There’s also a lot of confusion about what a “crop censor” camera is and a lot of different terminology used.

Let’s start with the term full frame – a full frame camera is a DSLR that has a sensor of approximately the same size as a standard piece of old-fashioned 35 mm film. Film was 36 mm wide by 24 mm high and for more than half a century the standard sized film for photography. If you dig around in your parent’s closets, you’ll probably find a 35 mm camera somewhere – everyone has one.

Let’s start with the term full frame – a full frame camera is a DSLR that has a sensor of approximately the same size as a standard piece of old-fashioned 35 mm film. Film was 36 mm wide by 24 mm high and for more than half a century the standard sized film for photography. If you dig around in your parent’s closets, you’ll probably find a 35 mm camera somewhere – everyone has one.

It was the standard for news photography starting in the 1950s as journalists moved away from Speed Graphics (with their 4 inch by 5 inch sheets of film) and TLRs (twin lens reflex, with their 120 mm wide rolls of film).

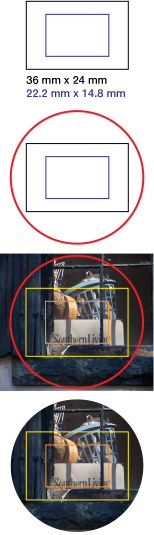

Crop sensor DSLRs, usually referred to as APS-C sized cameras, use a sensor that is smaller than an old piece of film, though Nikon and Canon have slight variations on the size. (Nikon, which calls this a DX sensor, uses a 23.6 mm by 15.7 mm chip, as does Pentax and Sony, while Canon uses a 22.2 mm by 14.8 mm sensor. Canon has also sold an APS-H chip, which is a little larger at 28.7 mm by 19 mm.)

At the top of the illustration at left, you can see the relative difference in size.

The first generations of cameras from all the manufacturers used some sort of a crop sensor chip. Because of the way digital sensors, either CCD or CMOS, are made, there is a higher failure rate and associated cost with larger chips. In the 1990s, when the first generation of cameras were being made, the technology didn’t exist to produce larger chips at a cost-effective price, hence the proliferation of APS-C cameras.

(Aside: Resolution, the amount of data that can be collected by a chip, is not directly related to the size of the chip. Common sense would tell you it is – if you have a smaller area, you can put a smaller number of individual light sensing cells. What has changed is the ability to shrink those cells tremendously, allowing very high resolutions from smaller sensors. There is a quality cost to this, though, as the smaller cells can have a harder time absorbing light, giving you lower quality in low-light situations. There is also a workflow issue as the higher the resolution, the larger the file size, the longer it will take to process images and the more storage you will need. Everything is a tradeoff.)

In 2002, Canon introduced the EOS 1Ds – the first full frame digital camera. Since then, Canon and Nikon have developed both full frame cameras and APS-C cameras as there has been a market for each.

So, if resolution isn’t a differing factor, what difference does this make? Full frame bodies are significantly more expensive than crop sensor bodies due to the cost of the chip, is there a reason to go full frame?

Let’s back up a moment and talk about what happens to focal lengths. First, focal length is focal length – it’s a measurement from the sensor to a point in the lens where the light crosses over when focused at infinity. Which is a lot of science, but think of it this way: the lower the focal length, the wider the field of view a lens can see and the greater the depth of field it will have at any given distance and aperture.

The phrase a lens can see is the key here for us. A lens is going to cast a circular image (see the second illustration at left), from which we crop a rectangle for our imaging purposes. Most lenses are designed to cast a circle a little wider than a full frame sensor can record, so an APS-C sensor, which is, by definition, smaller, is going to see a further cropped version of that circle.

Now, field of view is another term to think about as that defines how wide of an area we see. And this is where one of the most misleading terms comes out – magnification factor. Because a crop sensor camera sees a smaller segment of the imaging circle, many photographers refer to this as being a magnification.

It’s not.

So, some numbers. If I put a 300 mm lens on a full frame camera and a 200 mm lens on an APS-C camera, I end up with almost the same composition. (The “magnification factor” you’ll often hear is 1.5x.) Because the crop sensor camera is taking a smaller chunk out of the middle, while I may end up with the same resolution/file size, there is an optical difference in how the 300 mm lens will render the relationship between the foreground and background versus how the 200 mm, focused to the same distance, will render the foreground and background separation. The 300 mm lens will show more compression of the scene and give your subject more presence.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, if I put an 18 mm lens on an APS-C sensor camera, on a full frame sensor camera I only need a 28 mm lens to get the same field of view.

So which is better – full frame or cropped? My students know the answer here: It depends.

You have to factor in cost and image quality – not resolution, but the way your composition style works. For me, I like a lot of separation in my images – I really want my subjects to pop, so I have a strong preference for full frame cameras. (Although, my daily photo blog is shot with a half-frame sensored camera …)

The resolving power of the sensors is pretty close these days between the two sizes, but remember the density of the light sensing cells makes a difference in low light situations.

If I were to be shooting general news, I could probably get away with a crop sensor camera. And, for years, I did. I had to work to separate my subjects out from the backgrounds a little harder, but it was doable.

If I were doing sports now, I’d be on the fence. To get the separation I want I’d need to go to even longer focal lengths, so my preference would be full frame.

If I were doing landscapes or portraits, no question I’d want full frame. When you drop below about 50 mm, most lens will start to distort, making people’s noses appear larger than their ears. Again, I want that presence but not the distortion.

Which leaves us with cost. And, if you’ve read this far, you probably have some cost concerns. The top of the line APS-C body from Canon is the EOS 7D, and it runs about $1,400. The entry level full framer is the EOS 6D, which runs about $1,800. On the Nikon side, the D300s is around $1,450 and the full frame D610 is at $2,000.

In either system, you’re looking at a $400-500 gap from the top of the line crop sensor to the entry level full frame body – that can be a big gap to overcome.

There’s one more thing to watch out for when looking at which body you choose and that’s in the lenses. Almost every lens that’s made for a brand’s full frame camera will work just fine on the crop sensor body. But each brand has made a series of lenses specifically for their APS-C cameras and those will not work on the full framers. If the Nikon lens you’re looking at has “DX” in its name or on the barrel, it will not function fully on a full frame camera body. For Canon, watch out for the “EF-S” designation.

Those lenses tend to be consumer-grade lenses, but some of them can work in a professional’s kit. Just be wary if you think you’ll be stepping up to a full framer.