Gear Week: Strobes

Throughout the week, I’m writing a series of posts about buying gear. As we near the end of the semester with graduations and holidays approaching, the number of questions I get from students about putting together a kit skyrockets.

It is the bane of almost every young photographer and many seasoned ones – what to do with the dark. With the current generation of cameras having ISOs that approach the national debt, more and more shooters are just cranking up the gain and going all available light.

And, often, it looks terrible. Realistic, perhaps, but the image quality is rapidly approaching what a smartphone produces.

Blech.

There’s a story I heard years ago about a group of students who approached the legendary Robert Gilka and asked him his thoughts on strobes versus available light. His responses: “I’ll use any damned light that’s available.”

Having studied under Gilka, I believe that story to be true.

Learning strobes (or flash or speedlite, use whatever term you like) is one of the most technically challenging things in photography. You need to understand how batteries and capacitors interact, you need to understand how light is shaped, how light falls off, how light reflects, how light illuminates and how light shapes your subjects.

Get any of those wrong and your images look horrible. Get it right, though and … good gracious, the world is a stunning place to work.

The argument many photojournalists will make is that they don’t want to alter the scene, they don’t want to bring something to a moment that wasn’t there naturally. And I get that, I really do and, often, I’ll go to ultra low shutter speeds and very wide apertures to capture that setting.

But cameras and the human eye do not see in the same way. A camera captures one exposure, wherever thou place it. The human eye adjusts on the fly, allowing your brain to capture highlights and shadows without concern for the dynamic span between them.

Strobes, used well, allow you to compress that dynamic range and capture an entire scene.

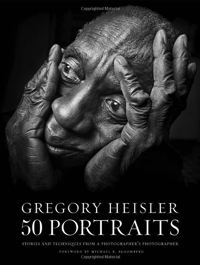

A few weeks ago I saw Gregory Heisler speak at the Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar and he is one of the masters of studio and portrait lighting. He was talking about his work and his new book, 50 Portraits, which I highly recommend. In his talk he said there are two ways to look at lighting – creating it from your own mind or, and I love this phrase, motivating the actual.

A few weeks ago I saw Gregory Heisler speak at the Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar and he is one of the masters of studio and portrait lighting. He was talking about his work and his new book, 50 Portraits, which I highly recommend. In his talk he said there are two ways to look at lighting – creating it from your own mind or, and I love this phrase, motivating the actual.

As journalists, I think we should be motivating the actual – looking for ways to increase the quantity of light without altering the quality of it. What I usually do and teach is motivating the actual. I just didn’t know what it was called.

Since we’re on media, another book you must get if you want to learn how to use small strobes is Joe McNally’s Hot Shoe Diaries. No one rocks a speedlite like McNally and this book takes you deep into the problematic weeds and through to the other side. A must read.

One last piece of media … two years ago, McNally and David Hobby, who goes by The Strobist online, teamed up for a bus tour across America teaching scores of photographers how to light. When they were done, they created a DVD of the event. I attended the Atlanta stop and was, expectedly, floored by how good it was.

Small Lights, Big Lights

Strobes come in different sizes and powers. What we will use mostly are generally called speedlites – they can slot into the hot shoe on the top of your camera, though you’ll want to get them off camera as much as possible.

The other option are lighting kits and they come in all shapes and sizes. You can put together packages from companies like Paul C. Buff which are very good and very affordable or go all the way to separate heads and power packs like the Speedotron system.

What you buy will be determined by what you’re shooting.

To start, though, you’re going to get into speedlites. The flexibility is great on these and will let you learn how to light without overwhelming your brain or budget.

Both Canon and Nikon have dedicated flashes for their systems. They will allow manual control (where you tell the flash how much power to push out) up through full TTL modes (where the camera and flash will meter light output through the lens as you make an image).

Aside: There is a lot to learn about strobes, how they work, how they don’t work, what they can and cannot do. Many years ago, I produced a short handout on flashes, which you can download and take a quick look at. Some of it is dated, but the core material is still of some value.

There are couple of features you’ll want in a speedlite. The first is power and that’s rated by what’s known as a guide number. (If you want, you can use the guide number of a flash to calculate exposures. It’s easy, but cumbersome.) The higher the guide number, the more light a flash can push out. More, as they say, is always better.

The second feature you’ll want is the ability to bounce the flash, meaning you can tilt the top of it up and some odd angle. This will let you, well … bounce the light of the ceiling so you can alter it’s direction and quality.

Third up is the ability to swivel the head so you can … bounce light off of the walls.

All of those assume you’re keeping the flash in the hot shoe on top of your camera.

Nikon and Canon have two usable levels of speedlites right now. For Canon, the big one is the 600EX-RT, which runs around $500. For years, on digital cameras, Nikon was eclipsing Canon on strobes – this is the flash that finally evened everything out. I have this and am very happy with it.

Nikon and Canon have two usable levels of speedlites right now. For Canon, the big one is the 600EX-RT, which runs around $500. For years, on digital cameras, Nikon was eclipsing Canon on strobes – this is the flash that finally evened everything out. I have this and am very happy with it.

The second level down for Canon is the 430EX II which is about half the price at $260. It’s a little smaller, but also significantly less powerful – it has a guide number of 141 versus the 600EX-RT’s 197.

On the Nikon side, you have the SB-910 at $550 or the SB-700 at $325. Again, the more expensive flash gets you more power – 157 to 128 on the guide numbers.

With any flash purchase, you need to pick up at least two other things. The first is an off-camera cord. Nikon and Canon make proprietary ones and they get a little pricey, $75, but it’s a must have.

The second thing I won’t leave home without is a gel set, and Rosco has worked with Hobby to create the Strobist Collection – 55 Cinegel color correction gels to help you balance your daylight-colored flash with whatever lights you find yourself under. At $25, it makes an excellent cheap holiday gift …

The Nikon strobes come with a little diffusion dome, and I love a diffusion dome, but you have to order them separately for Canon. I have used the StoFen Omni-Bounce for decades, it seems – great light quality and, for just $12 hard to beat.

What Else?

There is a world of strobe accessories out there. Both Canon and Nikon have remote possibilities built into their systems now allowing you to control multiple flashes from one position. (Nikon’s system is still a little better and, yes, I’m calling out Canon for not catching up on this.)

You can buy radio transmitters for longer distances or out of sight syncing. The Pocket Wizards are pretty awesome and some other folks speak well of the RadioPoppers, but I’ve never touched them.

There are lots of light modifiers out there, too. Things like umbrellas and stands are good places to start, especially if you’re going to do some portrait lighting. Adorama makes their own line of stands called Flashpoint which I’ve used and am happy with, along with their companion umbrellas. Note that to connect the two you’ll need a bracket.

Honl Photo makes a lot of cool light modifiers, their grids are very well regarded.

Honl Photo makes a lot of cool light modifiers, their grids are very well regarded.

Lastly, when you truly want to control your light, you’ll want to meter it independently. Sekonic is the last brand standing here and the L-308s is a great entry into this.

It’s a very dark world out there – light it up.