Starry, Starry Fakes

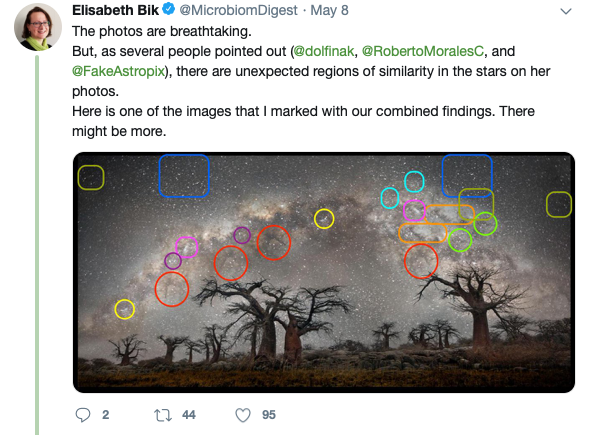

I may have a new hero – Dr. Elisabeth Bik, a microbiologist who has been looking at ethical issues in science journals, has turned her eye to some astrophotography published by National Geographic.

I may have a new hero – Dr. Elisabeth Bik, a microbiologist who has been looking at ethical issues in science journals, has turned her eye to some astrophotography published by National Geographic.

One of the great losses of the last 20 years has been the relationships between photo editors and photographers. It used to be that those relationships were cultivated, there were meetings and conversations and extended editing sessions where editors went over work, frame by frame, debriefing the visual journalist who was there in the field. They built up a rapper, they built up trust.

Those days are, for the most part, gone. Photo editors in some places are more akin to photo vacuumers – they are charged with sucking up as many visuals as they can to drive engagement and clicks in the digital realm. Without those relationships, even editors at publications as vaunted as National Geographic are going to get fooled.

Independent journalists, alone with their laptops and without a structured, ethical framework surrounding them, are going to have lapses. With the volume of work to do and the lack of interactions, what else do you expect to happen?

For publishers, they need to take a close look at these situations and ensure that protections are in place. Develop those relationships, get people on the phone, ask direct questions about the work – is this the way the camera saw this? Did you alter the original file? Did you alter the scene? Did you use any special effects? How did you get this access? Is there anything about this image I need to know? Do you understand the consequences of us finding a problem with this image later?

In her Twitter thread looking at lots of images, Dr. Bik asks a simple question: “Where does nature photography end and where does art start?”

I’d replace “nature” with documentary. And if you’re publishing documentary or journalism work, then you better be damned sure it’s real.